We entered the hall with solemn steps and took our seats. The group mostly comprised the beloved late ballet teacher’s university students. At the front of the room was a table with a photograph of a beautiful young woman. Of course she’d been young once, but it was odd to see a photo of Mrs. Dorsey from her youth. She’d been a dazzling star at the age of fourteen with the Royal Ballet, and through the eulogy we learned she’d managed to pack her whole life into a mere sixty years. This, too, came as a shock.

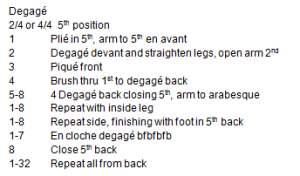

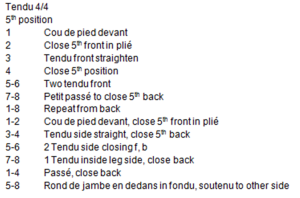

She walked with a cane which she’d given the name Betsy. Her hair was quite grey and worn pulled back at the nape of her neck. She wore horn-rimmed glasses and unflattering dresses with knee high hose, and taught every class in a pair of terribly old-fashioned lady’s shoes. If it weren’t for her clever combinations of steps we never would have guessed she’d ever been a ballerina. Most of the time she sat in a red leather chair and gave vocal instructions, tapping out the tempo with Betsy and sipping from a cup of hot tea. It was a challenge for me, as I’d never had a teacher who didn’t stand at the barre and demonstrate the exercises with grace and firmly accentuated calf muscles. Having to learn to translate the names of steps and positions of the arms into movement was, I realized later, a great opportunity for me. I began religiously writing down class combinations in dance journals, which I later used when I became a teacher myself. My desperate attempt to grasp the vocabulary in Mrs. Dorsey’s class was a great aid.

I was shy, uncertain about myself and not at all convinced I had what it took to be a ballerina. All I knew was that I loved to dance, and I wanted to do nothing else with such a passion. My father’s dream of going to London to study theater had been dashed by his parents when he was the age I’d been then, and I think he went out of his way to find opportunities for me. Mrs. Dorsey had been the one to write a letter of recommendation for me to attend Butler University as a high school student. I later saw her recommendation and was astonished it had been accepted (the student has ‘adequate’ ability), but I did have to endure an audition and I worked very hard and never gave up, even when I encountered a step I’d never seen before. Perhaps they saw potential, for I was enrolled in the program.

I worked with Mrs. Dorsey for a year and one summer. She’d told my father that the girls’ dressing room could be brutal and she was worried about how I’d stand up to the pressure. No one was cruel to me, ever. I was quiet, arriving for the 2:00 ballet class after having spent the morning at high school, then thirty minutes driving on the interstate to Indianapolis. Many days I also stayed for pointe class, and I was cast in The Nutcracker so had to stay for rehearsals as well.

One day, late in the year, we were doing attitude devant en tournant. It was rare that Mrs. Dorsey taught pointe class, and I think she was surprised by my rapid improvement. I somehow had developed strength and confidence enough to do this particular turning step well. She stopped everyone, got up from her chair, walked over to me and kissed the top of my head. Then, she turned to the rest of the class and said over the top of her glasses in her English accent, “She’s young…you don’t get kisses.”

I will never forget that day. Never before or again did a teacher ever compliment me with a kiss. After having taught ballet for many years myself, it never occurred to me to do the same for any of my students either, so I consider myself quite fortunate to have been given such a gift. This gift was all the self-assurance I needed to get me through the next ten years of my dancing career.

There were several teachers who said I wasn’t built right for ballet; my torso was too long and legs not long enough, or I just didn’t have what it took emotionally to withstand the pressures of a professional life in the field. But never did their words affect me. I had Mrs. Dorsey most days the following summer for a two hour ballet class and an hour of pointe. When we did well, she praised us. When we did not do well, she would only look at us over the top of her glasses and raise her eyebrows. She had lost a tooth that summer and tried very hard not to smile too hugely, but a few times she would lose herself in a happy moment and we’d see the gaping hole at the side of her top gums. It was endearing. I loved her so.

She lived close to campus and on a couple of occasions she asked me to give her a ride home. It was a bit embarrassing for me because I was driving a big, baby blue Ford pickup truck. She had an awful time getting in and out, and I was not well-mannered enough to know to give her a hand. She would smile at me with great affection, regardless, and waved as I drove off. She had told us once that she didn’t have much to do at her home. She would just look at the blank walls and choreograph combinations for our classes in her head.

After a break of a few weeks that summer, we returned to classes in the fall to find Mrs. Dorsey absent. We learned that she was in the hospital and she had cancer. News was that she cheered up all the nurses with her English humor, rather than being the one who was cheered. Only a few weeks later, she passed away.

And here we were, at a memorial service for our dear, sweet, Mrs. Dorsey. Probably an actual funeral had taken place already, or perhaps she was cremated. There was no casket, no trip to a cemetery for us that day. Her son was there and someone who offered words that didn’t come near to catching her essence. We looked upon the framed photograph of a lovely young woman and we each remembered how she’d touched our individual lives. I don’t believe there was a dry eye in the hall. I, for one, didn’t have enough tissues on hand.

For many years after, I would call upon Mrs. Dorsey from the great beyond, asking for her assistance with this audition or that piece of choreography. She never failed me, and I truly do believe that her spirit lives on and she is at my side whenever summoned. Sometimes I wonder how she managed to continue carrying on the tradition of teaching ballet for so many years. I found an article online that said she’d choreographed a Dickens ballet at Butler in 1959. That was 25 years before I arrived there. How many lives she touched can only be imagined. I just know that she had a magical effect on mine.

Somehow my father managed to learn of an estate sale at Mrs. Dorsey’s home near the university. He accompanied me there one day after class. We entered the small, brick home where she’d visualized ballet combinations while staring at her walls, and we walked among her things. It was strange to enter her personal world. Stranger still to find things of little value up for sale. We may not have been the only ones who went there for a sentimental trinket or two. I took home a pair of horn-rimmed glasses, a cane, and a plaque with a gold rose attached that reads:

All hearts grow warmer

in the presence of one who

gave freely for the love of giving

a giving that deepens and grows

ever unfolding new sweetness

as the blossoming of a rose.

I still have the plaque on my dresser, though I’ve since lost the glasses and the cane. No doubt it was given to her from one of her many adoring students.

One time I remember being in her class when no accompanist was there to play the piano. There was a record player available and some well-worn records, but she quickly gave up trying to make that work and employed her cane, Betsy, to pound out the rhythm on the floor. I’m sure she was exhausted by the end of an hour and a half of doing that, but she never let on that she was tired and she always had a lovely, peaceful face.

Now that I’m older, with three children of my own, working in the completely unrelated field of computer technology, I look back at Mrs. Dorsey and think about what she had said about the dance world being a cruel place. I did manage to get my bachelor’s and master’s degrees in dance and I did dance professionally for a short period of time. Many years I taught ballet to young people and enjoyed it tremendously. When my back started giving me problems I was unable to teach the way I’d always taught: standing at the barre in my leotard and tights with a long, black skirt and pale pink teaching shoes, demonstrating the steps with the best technical ability I had left. I suppose I could have asked for a demonstrator, someone who would stand in front of the class and show the steps as I wanted them executed, following my verbal lead. But it was too hard for me. Once I could no longer show the steps, I felt my teaching began to suffer. Maybe I should have called on Mrs. Dorsey for assistance then, before it was too late. We moved to a new state where no one knew me as a dancer or a teacher, and my talent seemed to diminish into nothingness. I have my children who give me great happiness, and I’ve worked at the bank now for nine years.

I did try teaching again, about a year ago. My back and my foot both gave me a lot of pain. It’s hard for me to do anything physical now, and I wonder if I’d been born in Russia if they would have filtered me out of the dance system before I’d ever started because my torso was too long, my legs too short. Still, I can’t wish for anything different than the experiences I’ve had and the teachers I’ve studied with or the students I’ve had the opportunity of teaching.

I’ve outgrown my shyness. I asked my father at one point if he would mind too terribly if I quit dancing. I think he was surprised at such a question. He says I made it farther in my career dancing than he ever made it in theater, but I don’t believe he’s right. He made a career of teaching, even if he wasn’t given the opportunities to perform himself at a professional level, and he has touched thousands of lives. I’m sure he would have been a fabulous actor, had he been given the right teachers and experience. Not all wonderful actors or dancers make wonderful teachers, either. I think Mrs. Dorsey’s dancing career was short-lived, although I don’t know this for certain. But I know she had a passion for teaching, as did my father. He never appeared to be disappointed in me, and I hope that she’s not disappointed in me either, for not learning to find passion in teaching from a red leather chair.